If you understand how supply and demand work, you have gone a long way toward understanding a market economy. — Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, Economics 19e, McGraw-Hill Irwin 2010, p.45

Here again we can see how absolutely nothing can be explained by the relationship of demand and supply, before explaining the basis on which this relationship functions. — Karl Marx, Capital Vol 3, Chapter 10, p.282

Introduction

Quotes in the following from Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, Economics 19e, McGraw-Hill Irwin 2010, p.60-61 except when noted otherwise. Emphasis in the original except when noted otherwise.

(1) The analysis of supply and demand shows how a market mechanism solves the three problems of what, how, and for whom. A market blends together demands and supplies. Demand comes from consumers who are spreading their dollar votes among available goods and services, while businesses supply the goods and services with the goal of maximizing their profits.

-

what, how and for what: Through the market the effect is produced that something is produced for someone. This is reinterpreted into a programme of solving the problem of what, how and for what that does not exist: no economic subject pursues these goals. The starting point of the analysis is to simply posit the purpose “satisfaction of needs”. There aren’t different approaches to solving this problem of which the capitalist mode of production is one.

-

blends together: The market only blends together what Samuelson rips apart. Rationally, the coordination of supply and demand is simply that the demand determines what needs to be done: one is the purpose, one is the means. These are not two independent forces – supply and demand – that need coordination in general, that have the risk of running off on their own. On a market there are forces of demand and supply but the market does not blend them together, as if they existed prior. This is neither an adequate account of economy in general nor of capitalism.

-

dollar votes: The image drawn is one of “consumer sovereignty” (p.45) on the one hand and business on the other hand. This identifies demand with consumers and ignores business demand. This is to maintain the problem of individual consumption is the one being solved here.

-

maximising their profit: Samuelson knows that businesses produce for a profit, but that doesn’t factor into the determinations below. The claim is one of an economy in service to consumers, encouraged by profit. Profit is a means, satisfaction of needs is an end. We shall see if the following analysis lives up to this claim.

Summary

- The market is good. Demand and supply are two independent forces.

A. The Demand Schedule

(2) A demand schedule shows the relationship between the quantity demanded and the price of a commodity, other things held constant. Such a demand schedule, depicted graphically by a demand curve, holds constant other things like family incomes, tastes, and the prices of other goods. Almost all commodities obey the law of downward-sloping demand, which holds that quantity demanded falls as a good’s price rises. This law is represented by a downward-sloping demand curve.

They clarify their notion of “demand”:

Our discussion of demand has so far referred to “the” demand curve. But whose demand is it? Mine? Yours? Everybody’s? The fundamental building block for demand is individual preferences. However, in this chapter we will always focus on the market demand, which represents the sum total of all individual demands. The market demand is what is observable in the real world.

The market demand curve is found by adding together the quantities demanded by all individuals at each price. – Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, Economics 19e, McGraw-Hill Irwin 2010, p.48

-

relationship: The claim is that prices (independent variable) determine demand (dependent variable).

-

individual preference curve: What the individual customer wants can be depicted by a curve, market demand is merely the sum of individual demands. They have a preference for some magnitude (U) of good (A) at price (X), just as much as some magnitude (U+ΔU) of the same good (A) at price (X-ΔX). Small magnitudes of a given good for a high price are as preferable as a large magnitude of the same good at a low price. This is nonsense – you want a fridge you want a fridge, you want a Playstation you want a Playstation – but enables to “solve” the coordination problem by having two lines that can intersect.

-

market demand preference curve: These hypothetical individual demands are then added up. Even arguing with market demand preference, how many cornflakes can they eat? Isn’t there a limit to how many they’ll buy? When prices of cornflakes fall, people don’t just buy more cornflakes, they buy enough to have enough cornflakes. In this model all content is extinguished: why and how people buy commodities, that acts of exchange represent actual relations of production and consumption.

-

other things held constant: On the one hand, this declares that other things influence the demand, but they are excluded from consideration. Then, the authors conclude that the thing they don’t exclude has an effect: the curve of price impacting demand by excluding everything else. For example: “There exists a definite relationship between the speed of the car and its weight, other things held constant.” What have you learned about the thing that makes a car go fast in this statement. What we’d need to know is why we are holding what else constant, why decide that price is the determining factor? Why not the relations of production/consumption, i.e. that demand is determined by what e.g. people need to live.

The claimed law – prices determine demand – is false.

(3) Many influences lie behind the demand schedule for the market as a whole: average family incomes, population, the prices of related goods, tastes, and special influences. When these influences change, the demand curve will shift.

-

family income, prices of other goods: when family income is held constant but prices change, the limited family income is confronted with prices, means and needs do not fit together. The substitution effect tells the same story: product A is substituted by product B because of limited purchasing power. When prices rise some people are priced out of a commodity. and When incomes fall some people are priced out of a commodity.

-

influences: Price determines demand except when it doesn’t. When they then list what influences it they give a motley list of stuff – including the weather. This way we learn that everything influences everything.

The claimed law – incomes determine demand – is false, but corresponds to something observable: poverty of the masses.

Summary

- Prices determine demand.

- Incomes determine demand.

Together: demand is a function of what something costs and how much money people have to spend on it. As a theory of prices this is absolutely useless. This also tells a very different story to “dollar votes”, the limitation of these votes, the poverty of those sovereigns, is the key thing both in thesis 2 and 3.

B. The Supply Schedule

(4) The supply schedule (or supply curve) gives the relationship between the quantity of a good that producers desire to sell—other things constant—and that good’s price. Quantity supplied generally responds positively to price, so the supply curve is upward-sloping.

-

desire to sell: Producers want to sell (U) items of commodity (A) for price (X) just as much as they want to sell (U+ΔU) items at price (X-ΔX).

When a producer can’t get the price that it wants, needs or considers necessary, it withdraws the supply from the market, the exchange doesn’t happen. Luxury sports cars are not sold at the price of pints of milk because supply and demand will it so. If they cannot be sold for a specific price, they simply aren’t sold, production of them seizes. There is no smooth curve of price/magnitude expressing indifference: all the same. There are prices that enable a profit and prices that don’t. A producer wants to sell for a price relatively high compared to cost, the bigger the difference the better.

The only moment getting close to this is crisis, everybody wants to sell to get their hands on money. But this is not the scenario they’re talking about: the break down of the economy.

-

mirror: they set up demand and supply schedule as mirrors, one downward and one upward sloping. However, the former has some asserted preference as the thing that’s thing longed one, the latter has profit as the thing being optimised for.

-

quantity: also at constant prices extension of production makes sense: if you make £1 profit per widget, selling 1,000 widgets instead of 500 means earning £1,000 instead of £500. Yes, if you can make even £1,200 that’s all the more reason, but it is not true that we have supply as a function of price. This mistakes enables the intersection later.

The claimed law – prices determine supply – is wrong.

(5) Elements other than the good’s price affect its supply. The most important influence is the commodity’s production cost, determined by the state of technology and by input prices. Other elements in supply include the prices of related goods, government policies, and special influences.

-

cost: It is the difference between cost and price that drives supply not absolute cost. It’s not true that cheaper production cost mean increased supply, cheap production cost relative to a high price are a further reason to increase production. If understood this way the law is false, but what they mean is: at a given price, the cost influences profit.

We’ve also therefore learned a completely different determination of prices: how long it takes to produce something: “It takes far fewer hours of labor to produce an automobile today than it did just 10 years ago. This advance enables car makers to produce more automobiles at the same cost. To give another example, if Internet commerce allows firms to compare more easily the prices of necessary inputs, that will lower the cost of production.” (p.52) They cannot and will not sell for less than cost + profit, but Samuelson drops profit despite introducing it earlier.

-

most important influence: price determines supply except when it does not. They want to say, if the gap between cost and price gets bigger, production is encouraged, when the gap between cost and price gets smaller, production is less worthwhile. This gap is profit, so the whole thing boils down to observing that companies produce for a profit without ever saying it.

The claimed law – costs determine supply – is wrong: profit does.

Summary

- Prices determine supply.

- Costs determine supply.

Comment

Together: The difference between cost and price determines supply.

C. Equilibrium of Supply and Demand

(6) The equilibrium of supply and demand in a competitive market occurs when the forces of supply and demand are in balance. The equilibrium price is the price at which the quantity demanded just equals the quantity supplied. Graphically, we find the equilibrium at the intersection of the supply and demand curves. At a price above the equilibrium, producers want to supply more than consumers want to buy, which results in a surplus of goods and exerts downward pressure on price. Similarly, too low a price generates a shortage, and buyers will therefore tend to bid price upward to the equilibrium.

-

equilibrium: is a tautology. The quantity demanded just equals the quantity supplied. What is the quantity demanded: market demand, which is observable, i.e. effective demand observed on the market. Thus, by definition all demand, defined like this, is always satisfied, there is never more demand, since that demand wasn’t demand can’t be observed. People starving to death: all effective demand is satisfied.

-

intersection: this explains the mistakes they made earlier, having an upward and a downward sloping curve means they must intersect at a single point (that isn’t infinity).

-

quantity demanded equals quantity supplied: no economic subject has this purpose. Producers do not direct the price according to demand, but according to whether it makes them a profit. Every crisis sees unfulfilled demand on the one hand and heaps of unsold commodities on the other. They then don’t go: “well I sell dead cheap so that market clearing happens”.

Example:

# widgets sold unit price # widgets made unit cost profit 1000 £12 1000 £8 £4,000 900 £12 1000 £8 £2,800 1000 £10 1000 £8 £2,000 -

determinations: The logic so far is thus:

- the price determines the demanded quantity

- the price determines the supplied quantity

- supply and demand – at a given price – determine now a price called the equilibrium price

- this price makes the two magnitudes match.

First, they invent many different unreal prices in addition to the real price, i.e. that are not observable. The reason why the price that exists exists is that other prices would be too high (consumer) or too low (producer). Now, the exchange at the price which exists produces the equilibrium price, which is the price that matches supply and demand, which merely means labelling the price that is as the equilibrium price.

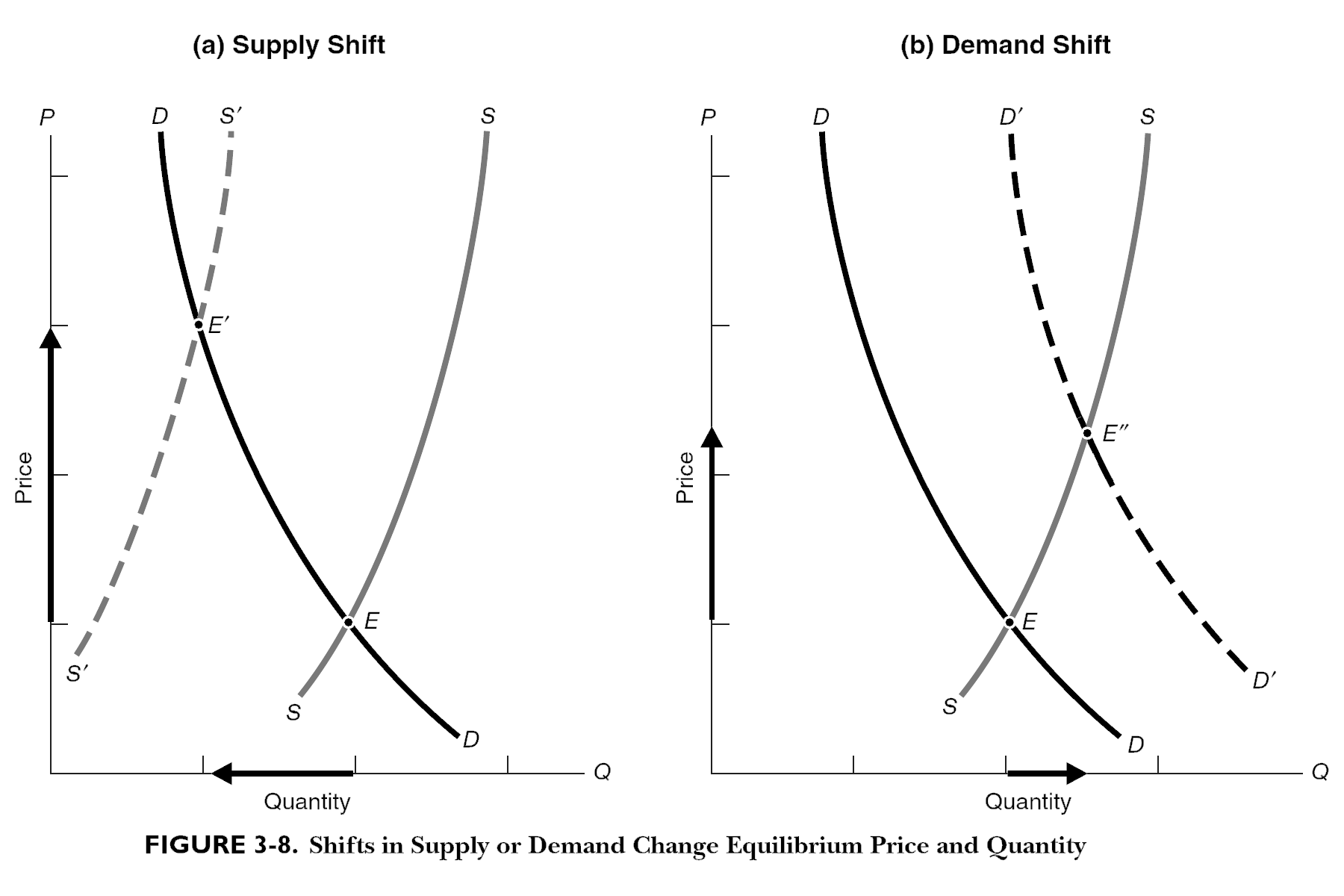

(7) Shifts in the supply and demand curves change the equilibrium price and quantity. An increase in demand, which shifts the demand curve to the right, will increase both equilibrium price and quantity. An increase in supply, which shifts the supply curve to the right, will decrease price and increase quantity demanded.

- equilibrium is stable: in their theory only external impacts can take the market out of equilibrium: incomes fall, costs change. Why do incomes fall? Why do costs fall? It’s because capitalists optimise their profits, they are not happy with equilibrium of market clearing prices. You don’t need a shift in the curve for increased supply.

(8) To use supply-and-demand analysis correctly, we must (a) distinguish a change in demand or supply (which produces a shift of a curve) from a change in the quantity demanded or supplied (which represents a movement along a curve); (b) hold other things constant, which requires distinguishing the impact of a change in a commodity’s price from the impact of changes in other influences; and (c) look always for the supply-and-demand equilibrium, which comes at the point where forces acting on price and quantity are in balance.

-

a and b: Distinguish between increases in supply caused by a price change from increases in supply not caused by a price change.

The circular reasoning formulated as a caution: everything influences everything, so you have to understand what caused what.

-

c: don’t know what this means.

-

caution: this is also their critique of false applications of supply and demand.

(9) Competitively determined prices ration the limited supply of goods among those who demand them.

- ration: Nothing is rationed, people manage to sell their shit or they don’t. Nothing is allocated. At the end, there is a result. This pretends there are different ways of accomplishing the same thing – rationing – and the market economy is one way amongst many to go about this. But rationing is not the purpose of the economic subjects: they look after their own moneyed interest. The claim is simply: prices mean that those who can pay them, can pay them.

Summary

- Prices determine supply and demand. Supply and demand determine price.

- Changes in supply resp. demand changes prices and demand resp. supply.

- Caution to distinguish price (→) supply/demand and supply/demand (→) price.

- The market is good. Same as 1.